Outgrowth (2024), Deconstructing Patriarchal Ideologies Embedded in Femininity and Nature

- Fiona Donovan

- Dec 10, 2024

- 9 min read

New York City’s towering skyscrapers and rigid urban grid exemplify humanity’s domination over the natural world, a dominance mirrored in patriarchal control over women. The city’s constructed landscape reflects the same hierarchical systems that reduce both nature and femininity to objects for exploitation. This exploration centers ecofeminism as a framework to examine how patriarchal ideologies have devalued both women and the wider natural world. Drawing from theorists Val Plumwood, Carolyn Merchant, and Greta Gaard, I challenge binary thinking and explore the underpinnings of these systemic structures. Through an analysis of paintings by Thomas Cole and Paul Gaugin, I highlight how the art historical cannon has reinforced these narratives, and position my own artwork as a counter-narrative. Deconstructing patriarchal ideologies requires theory and imagination simultaneously. Through this combination, this essay seeks to challenge the logic of domination driving social and ecological crises, while proposing a future driven vision for resistance and renewal.

The intertwined domination and degradation of nature and women is a recurring theme in patriarchal ideologies, deeply embedded in historical narratives. Ecofeminist Val Plumwood identifies a series of binaries that underscore this logic of domination and othering, positioning reason/nature, male/female, and master/other. “Everything on the ‘superior’ side can be represented as forms of reason, and virtually everything on the underside can be represented as forms of nature” (Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, 43-44). These binaries help to assert a ‘logic of domination’ where patriarchal reason first diminishes femininity and forms of nature, with the goal of othering, making them feel peripheral. The dominant perspective views “the other” relationally instead of recognizing their autonomy. The objectification of “the other” can be found in the foundation of its identity, as it is predicted by its usefulness to the ‘master’. Finally, this process of thought reduces and homogenizes “the underside”, alienating the group and further distancing it from its “normal” counterpart. These processes result in the subordinate “other” lacking autonomy, ever in service of the “superior” (Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, 48-53). The logic of domination denies the complexity and autonomy of both nature and femininity, reducing them to commodities. The pervasive masculine framework bolsters and encourages wider systems and processes of control, inaccurately framing them as inherent, instead of the current present dominant powers designed to uphold the historical and current dynamics.

Greta Gaard critiques the current masculine approach to the climate crises which prioritizes seemingly short-term technological solutions, such as the invention of electric vehicles, over long-term systemic change. She argues that “queer feminist posthumanist climate justice perspectives” offer a vocabulary to decenter the “superior” masculine, and center marginalized voices allowing solutions that are more stable, permanent, and far reaching (Gaard, Ecofeminism and Climate Change, 23). This theoretical framework aligns with Val Plumwood’s critique of instrumentalism, which describes the societal reduction of nature and marginalized groups to “standing reserves” for exploitation, deprived of autonomy and intrinsic value (Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, 226). If one centers relationality, as Gaard does, they can begin to reverse the dominant, exploitative masculine structure focused on singularity and selfishness, and instead adopt solutions grounded in equity, care, and reciprocity.

Carolyn Merchant’s critique of patriarchal domination in Reinventing Eden, develops an analogy between the biblical story of Adam and Eve and the systematic control of both women and the natural world. Merchant claims that the eating of the apple by Eve, which resulted in the couple's expulsion from God’s garden, has been extrapolated as the root cause of humanity's banishment to the unruly, feminine nature: one that needs taming to restore order. This is reflected in the determinism to “reclaim paradise” demonstrated in acts of environmental conquests, usually hailed as testaments to human ingenuity but is actually rooted in patriarchal ideology. This control over nature thus reflects the greater societal desire to control women, reflecting a broader dualism that equates femininity with chaos and inferiority.

The necessity of confronting these systemic injustices is further underscored by Patsy Hallen who writes “ecofeminists set themselves two principal tasks: to expose this ‘logic of domination’ and to seek alternatives that bring us to our senses” (Hallen, Recovering the Wilderness in Ecofeminism, 225). Her emphasis on reconnecting with nature through her courses in the Australian bush, exemplifies the landscape as an integral part of human identity instead of a resource, binding the mindscape and landscape as one. In Hallen’s framework, nature becomes an equal participant in the narrative of existence, forcing us to develop a different relationship with the marginalized. This recognition disrupts the binaries of patriarchal thought, such as mind/body and culture/nature, in favor of interconnectedness.

Art history provides a framework for visualizing patriarchal thought, in particular, the way in which it has determined representations of nature and the female body. Thomas Cole’s The Oxbow (1863) illustrates the duality of tamed and uncontrolled landscapes, positioning the cultivated half of the landscape as a testament to human mastery over nature. The artist's self inclusion in the wild, left half of the composition, suggests a contemporary coexistence with untamed nature, reinforcing the narrative that humans can survive outside control only long enough to subjugate it. Similarly by Cole, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1827-8), dramatizes the consequences of feminine transgression, portraying nature as a chaotic force requiring masculine intervention to restore balance. The glowing right side of the composition depicts Eden as an idyllic sanctuary of order and controlled nature, contrasted with the dark, untamed wilderness on the left. The painting’s moral narrative ties the expulsion from Eden to Eve’s transgression, aligning the wildness of nature with the perceived dangers of feminine autonomy. The chaotic left side of the painting triggers a call to control the wilderness, and by extension, women, as necessary for restoring balance. Yet still there is a simultaneous fear of, and dependence on, the vitality of the natural and feminine.

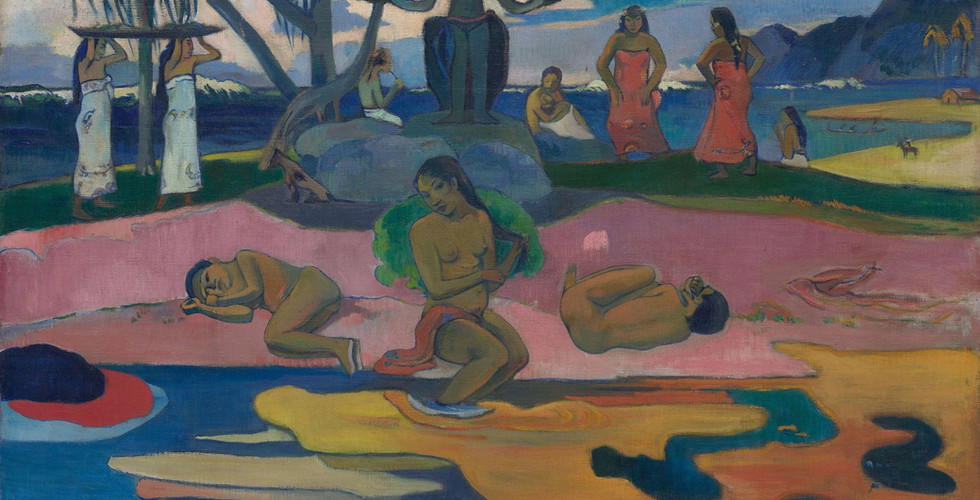

Paul Gaugin’s Mahana no Atua (1894) furthers this narrative by presenting both women and landscapes as submissive, awaiting domination. The work exemplifies ‘primitive art,’ where both the figures and the environment are depicted under an inferior lens, rationalizing their inevitable domination. The women’s passive postures and their integration into the landscape blur the boundaries between human and natural, reducing both to objects of control. This aligns with colonialist and patriarchal ideologies, which frame non-European societies and nature as resources to be exploited. Gauguin’s use of vibrant colors and sensual forms romanticizes this exploitation, disguising its violence under aesthetic beauty. This theme is reflected in his Self Portrait (1889), in which he places himself with a snake and apples, referencing Adam and Eve and speaking to Carolyn Merchant. The halo above his head positions him as a figure of moral superiority, reinforcing a narrative where man, through supposed restraint and control, holds power over nature and women. The snake in his fingers symbolizes his self-perceived role as the savior of humanity, a necessity to recover Eden. Together these works reinforce an intertwined patriarchal and colonial perspective that reduces the ‘other’ to resources for domination.

The work I created, Outgrowth (2024), depicts a nude woman drawn in expressive blues, pinks, and oranges, that emerges from unruly, abstracted growth. She is framed by grayscale, graphite pixels that absolve into her explosive aura, symbolic of the tension between patriarchal control and liberated vitality. The figure is shown removing a blindfold, a motif of Lady Justice (Greta Gaard, Ecofeminism and Climate Change, 20), visually claiming her knowledge of domination and personal autonomy. This act represents the dismantling of patriarchal structures that have conventionally blinded both women and nature to their own inherent value. Reclaiming the duality of nature as pictured by Thomas Cole, the untamed nature is something to be celebrated rather than feared. I situate the figure within this growth to challenge the concept of nature as merely a backdrop. Instead, it becomes a living force intertwined with the figure, representing not just the resilience of the natural world, but also the possibility of human reconnection with it. This relationship becomes a path toward healing, both for the individual and the environment, offering an alternative to the logic of domination that has shaped our histories. The gray pixels, stark and mechanical, represent a masculine desire for natural and feminine control through objectification and technology. In contrast, the fauvist color palette used for the figure reclaims the vibrancy once wielded by Paul Gauguin, transforming it from a tool of objectification into one of empowerment. The stark contrast between her vivid aura and the subdued, monochromatic surroundings emphasizes the vitality of the feminine and natural world, breaking free from imposed hierarchies. The natural wooden backdrop further anchors the piece in ecofeminist ideology, symbolizing a return to organic materiality and a refusal of artificial control. Much like Gaard’s call for posthumanist perspectives, my creative practice seeks to reimagine a world where both nature and femininity are seen not as tools but as autonomous forces with their own inherent worth. Such a perspective resists the masculine urge to dominate, and offers a vision of renewal that values interdependence rather than hierarchy.

Ecofeminist theories have become profoundly personal to me, as my move to New York City created a paradigm shift in the way I understand and relate to patriarchal systems and their pervasive influence. Living in an environment where both the mindscape and landscape seemed to be defined by control and exploitation, I found myself drawn to the cycles that reflected the very structure I aimed to critique. Various experiences made me feel trapped by expectations that reduced my identity to a resource within systems I believed were inevitable. Repeatedly, I adopted those systems in search of security but instead reinforced patriarchal dynamics. Escaping these cycles required a deliberate act of disavowal of the logic of domination in which both my external surroundings and internal beliefs were radically flipped. I found that the theories of ecofeminism, their analysis and critique of the patriarchy, resonate with my journey to independence. Today, my creative practice reflects this reclamation and presents a vision of femininity that reimagines patriarchal narratives, and seeks to inspire others to question and dismantle these systems.

Bibliography

Cheetham, Mark A. Landscapes into Eco Art: Art and the Environment in the

Anthropocene.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

This source discusses the land art period that emerged in the United States in the 1960's. It followed the expressionist period, where art was seen as an expression or residue of an artist's action, and emphasized a process rather than a final product. As an example, Cheetham looked at Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, where a trench was cut into a Nevanda mountain side. This generated critiques against the environmental impacts of land art as it heavily manipulates the land. The artists often viewed the land as theirs to do what they choose, and the result as a monument to their creative genius. This theory responds to misogynist narratives on objectification and physical manipulation of women.

Gaard, Greta. "Ecofeminism and Climate Change." Women's Studies International Forum 49

(2015): 20–33.

This data heavy, informative source, in a way, utilizes the ‘rational’ language of the patriarchy to both highlight the disproportionate effects of climate change and provide a lens through which decenters masculinist biases. Gaard uses an intersectional vocabulary to illustrate her points, looking to gender, class, race, and sexuality as hallmarks of the othered.

Hallen, Patsy. "Recovering the Wildness in Ecofeminism." Women's Studies Quarterly 29, no.

1/2 (Spring–Summer 2001): 216–233. Published by The Feminist Press at the City

University of New York. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40004622.

Patsy Hallen overviews her courses immersed in nature, and why they are crucial to a deeper understanding of the othered. Hallen draws correlations between the mastery of nature to the patriarchal ego, connecting the landscape and mindscape. This work converses with the writings of Val Plumwood, which spells out the logic of domination, and puts it into an ecological perspective.

Merchant, Carolyn. Reinventing Eden: The Fate of Nature in Western Culture. New York:

Routledge, 2004.

Carolyn Merchant examines the similarities between the control of nature and the control of women, in comparison to the biblical story of the Garden of Eden. Implied in Adam and Eve’s narrative is the fault of Eve for the pair's exile from Eden. What faced them was unruly mother nature, that is still ‘paid for’ today, as humans actively seek ways to control both nature and females, to reclaim paradise. In controlling nature, these methods are often conquering acts, rather than harmonious solutions, reflecting patriarchal views.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Visualizing the Anthropocene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Here, Mirzeoff discusses depictions of pollution in impressionism. Monet, for example, romanticized it, put it under a light of something beautiful, something natural. This source also analyzes landscape as a form of media, creating discourse within the act of framing a scene. This process creates a border so it is more palatable, as well as creates value in a section. This correlates to imagery of impressionist nudes, that often fragmented the female body to make it look more controllable and consumable.

Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Chapter 2, "Dualism: The Logic of

Colonialism." London: Routledge, 1993.

This source provides the theory of dualities, a relationship between a ‘superior’ and ‘underside’. It outlines the oppression of the undersides through steps following backgrounding, radical exclusion, incorporation, instrumentalism, and homogenisation. It then provides a counter method of equality that decenters the ‘master’ figure from traditional discourse. Plumwood speaks on reclaiming feminine identity from the patriarchy, while still maintaining parts of its traditional qualities.

Comments